Through the Kaleidoscope | Recent Works of Akkitham Narayanan

Through the Kaleidoscope | Recent Works of Akkitham Narayanan

30th July 2011 - 25th August 2011

Art Alive Gallery, S-221 Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110017View WorksPainter Akkitham Narayanan squeezes colour directly from a tube to the canvas, inviting risk, spontaneity and experimentation. When compared with the calculated mixing of colours on a palette that most artists engage in, each of his paintings appear to be a passionate, accidental experiment with colour.

Akkitham hence believes his work to be calculated accidents. ‘Calculated’ because the Paris- based, Kerala- born artist, spends months preparing for those spontaneous ‘accidents’ of creation by making preparatory drawings on smaller canvases and paper. When he arrives at his moments of conception, it usually takes less than three or four days to complete the works.

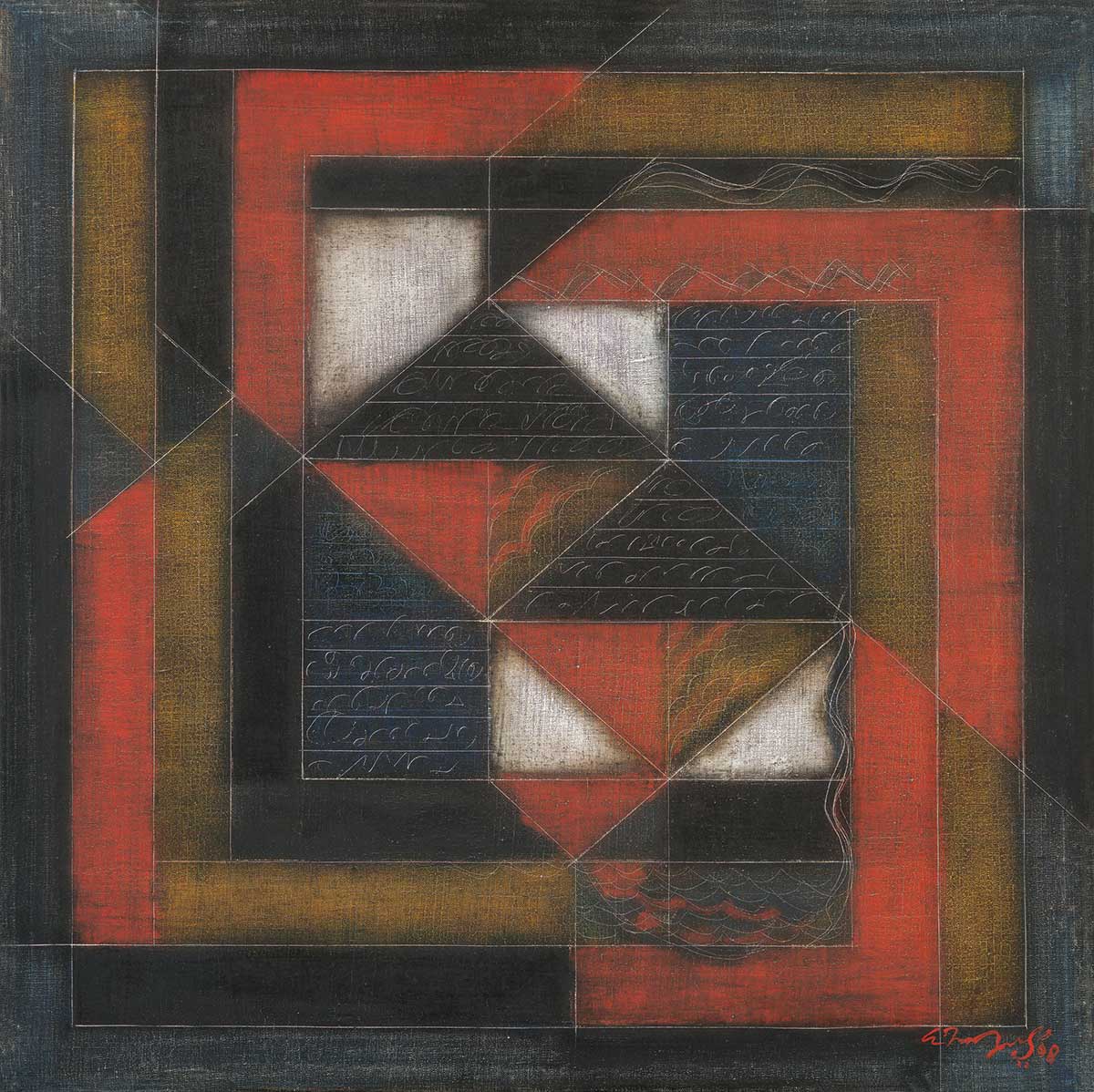

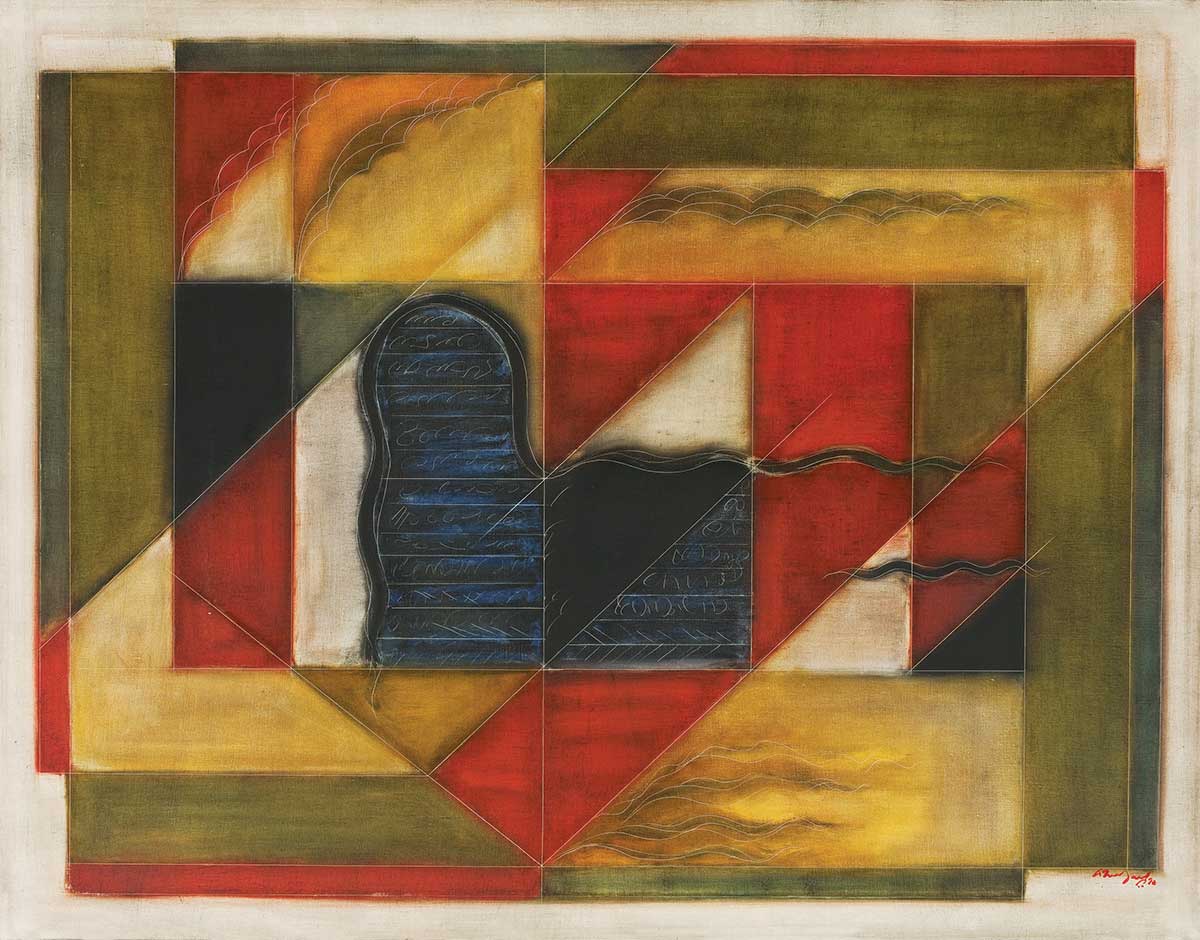

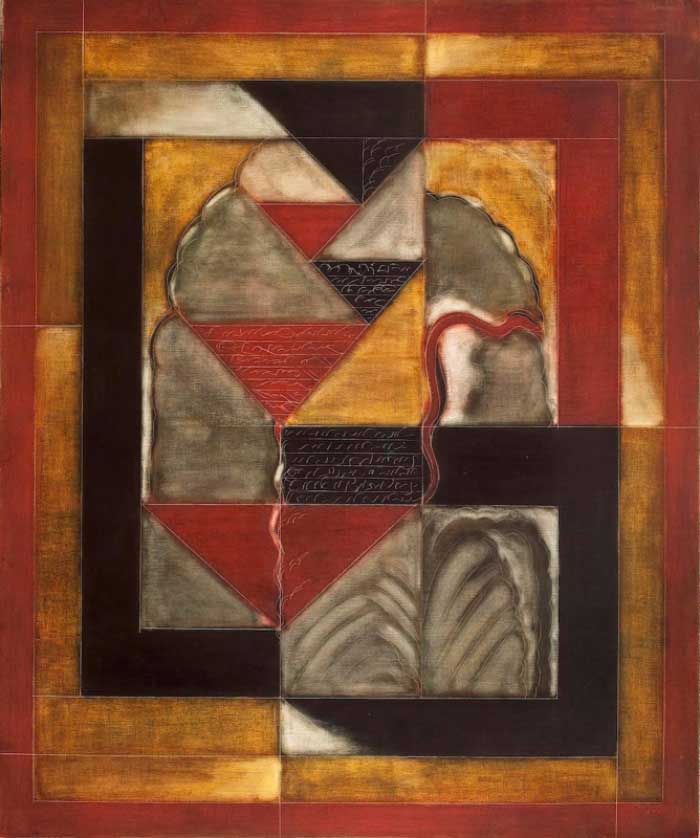

After many months of contemplation, Narayanan works with an accelerated momentum where he taps into his subconscious to summon colours that collide, while giving birth to forms that resemble solid, geometric patterns, packed tightly together in a grid. He intersperses these with diaphanous natural forms like rivers and trees. He also uses other stimuli like text from the Rig Veda and his brother’s Malayalam poetry, but often the text is used as a symbol or pure form rather than a word that is meant to be read cogently.

This current suite of 20 paintings have been executed over a period of three years 2009 to 2011 during which his palette has moved toward restrained, darker colours with a stress on ochre, green, reds, yellows and a scattering of blues and greens. This toning down of palette, in some ways is a return to his early preference for black and white. One could say that the artist has come full circle.

The final body of work; reflects his technical acumen that rises from long years of engagement with oils. He now paints directly on the canvas applying a thin layer of colour. After the first layer has been applied, the artist merges them with a larger brush going over it till he arrives at the tone and colour that best expresses the mood of the form and the moment he is striving to capture. He then removes the excess paint with a palette knife and cleans the surface with a cotton rag. Finally with a sharp tool he etches white lines into the canvas that defines the form further. It is only then that he steps back to review the finished painting. This entire process echoes the meticulousness and hard labour similar to that in printmaking even though process wise it is actually the reverse.

Currently, he sees his works as visual diagrams that are still, in some way, anchored in his early Cubist paintings, even though they have changed drastically in avatar and expression. Narayanan comments that a work of art never really breaks its ties with representation, irrespective of how ‘abstract’ it may strive to be. The prior knowledge of an experience guides one to look for forms even in a splash of colour or an arrangement of lines.

In Narayanan’s work the association with recognisable forms is far more pronounced and deliberate than that of an artist who engages in colour- field painting. Referencing the style of German Abstract Expressionist painter Paul Klee, Narayanan’s endeavour as a painter is mainly to recall and enhance the essence of the experience rather than the experience itself.

This distillation brings about a refinement and purity of form that rises above the form itself. Each painting then becomes a presence rather than a simple arrangement of squares, circles and triangles. They evoke a mood and possess a personality. The works have the power to stir up a sound like a Vedic chant that induces a meditative mood, acting as repose from the mundane nature of everyday life.

In that sense, they could be seen as recreational; however, their purpose is intended for a higher nature than mere recreation. It is in fact to stimulate a sense of the sublime. The works move towards oneness with the self and the other, the divine and the human. It is toward this end that these paintings strive and intervene.

While they derive their stimulus from the Rig Veda, the paintings are not overtly religious. If nothing, they move away from the symbolism and iconography of religion. Instead, the works of art strive to create a pan spiritual experience that is not anchored in one religion or region, even while using specific texts. There lies his journey into abstraction where the forms themselves mingle with the ideology that gave birth to them in the first instance.

For those who are unfamiliar with his work it may come as a surprise that he began painting small format works in watercolour–just to be different from the prevailing large format works that the old masters in Paris pursued in the late 1960s.

Narayanan’s sojourn to France began when the painter received a scholarship in 1967 from the French Government and he left his motherland to pursue his art on foreign soil. He and his contemporary, K. Viswanadhan, were influenced more by mentors like the pioneer painter KCS Panicker, one of the founder members of the Cholamandal Artists’ Village in Mahabalipuram, Chennai (Madras), in 1966.

In an attempt to reclaim an indigenous sensibility, the Cholamandal group moved towards a style they called Neo Tantrism, one that helped them move away from the European masters and brought Modernism to South India. The ideas of Neo Tantrism was propounded by theorist Ajit Mukerhjee and adopted by artists like Biren De in Kolkata, Jyoti Bhatt in Baroda and KCS Panicker in Chennai.

While there have been several writings on the Cholamandal Artist’s Village that have been critical of its attempts to create a bourgeois, modernist space within what was essentially a traditional craftsman driven space, it was the spirit and sentiment of the late 1960s that drove this initiative. In fact one could say that the ‘village’ was in step with the overarching, nationwide attempt of the times to reclaim all that was Indian and integrate to it with the lingering influences of a Post Colonial India. Hence India looked beyond its borders for inspiration it did not lose contact with its roots.

In its current avatar the Cholamandal Artist Village now has a modern art gallery, a sculpture court, library and residency space for artists. Clearly Panikar’s vision has been kept alive by his son Nadagopal and other forerunners of the movement.

It is important to locate the young Akkitham within this socio-political context to understand why he began painting in a Cubist style, preferring black-and-white charcoal over colour. He was heavily influenced by German Expressionist painters like W Kandinsky and Paul Klee. However while these two German masters were known for their flair with colour, Akkitham preferred charcoal for its ‘sober moody quality’.

Later he moved away from direct figuration, preferring the symbolism and mysticism of Neo Tantric art, even while studying in Paris. We see this in an artist like Amrita Sher-Gil who revisited her roots when she returned to India and later in artists such as S H Raza and Ram Kumar, both of whom have studied in Paris and both of whom never lost contact with their native soil.

Like them, Narayanan also turned to the miniatures and the cave paintings of Ajanta that go back as far as 200 BCE, even while cherishing the magic of 19th century artists like Klee and the early cubism of the French painter Paul Cézanne.

Over the years Narayanan strove to orchestrate all these influences into his psyche so that they arrive on his canvas as an equal music; one that is perfectly balanced.

His subjects have always ranged from landscapes and architectural drawings to the fecundity of foliage and trees. The hard- edged staccato of manmade structures like modernist buildings and antique churches -later represented by geometric forms-have always been complimented by the soft, lush contours of vegetation, the cushioning of fluffy clouds and the sinuous bend of a winding river.

For Akkitham, this contrasting nature of forms is an ideal juxtaposition that brings the two worlds of nature and man together in harmony. We see this as a persisting leitmotif that has stayed with him over the years manifesting in his current canvases. Interestingly the human form has hardly ever made an appearance on his canvas although the presence of humanity is implicit in every work. This presence is usually located at the centre of his canvas is like the fulcrum that keeps in balance the two worlds, one that is made of concrete and the other of sky and earth.