A Perspective on Process - By Geeti Sen

Painting is most significantly, a process of realisation: from that initial point of stimulus, reverie or impassioned response to its transposition into the mind’s eye of the artist and her/his tentative experiments – to a stage when the image is brought ‘to life’ on paper or canvas. This is the final moment of realisation; but the journey remains equally relevant.

This book differs from others in that it concerns itself less with the finished work, its interpretation and critical assessment. Not a marker of art movements, manifestos, schools and styles and political ideology, each valid in contextualising the image, this book brings us instead to face the artist as an individual. It is the first on contemporary Indian art to explore experiments and experiences along the artists’ journey. Nemai Ghosh, celebrated photographer for his stills of Satyajit Ray’s films, now embarks on this ambitious project of situating ‘the artist at work in the studio’. His camera is focussed on that private space of introspection or feverish activity, with the artist in solitude and in dialogue with his work.

The creative process is not programmed beforehand, or easily divulged even to those who create, who do not fully comprehend how their work evolves… It becomes then, a fascinating experience to watch them in the studio. Their work becomes a process of individuation, inspired by personal experience and a quest to discover the authentic. Krishen Khanna comments: ‘For me the area that has to be painted has to be cultivated like a piece of earth which will produce a rich yield…The image, or the idea of the image is planted rather like a seed in prepared ground which is ready to receive it. It surfaces and often enough does not correspond to what I had thought it would be.

A painting has its own compulsions, a language and a grammar developed by the artist — which we describe not by that much loaded term of ‘style’ but as an idiom peculiar to the artist – flowing from his temperament, environment and history. Idioms are personal quirks or mannerisms: they dictate the methodology: the choice of medium, the tools used, the brushes thick or thin, the way pigments are applied. They might show a preference for the curving nonstop line to inscribe a sultry sensuous woman, in the case of Jogen Chowdhury; or the layering of thick impasto colors directly on canvas to ‘discover’ his inner landscape, for Ram Kumar; or the quick smudging of black ink with fingers to effect the vibration of trees, by Gulammohammed Sheikh.Some prefer the brush or palette knife, while Satish Gujral may on occasion use just a pencil, patiently absorbed for hours into creating a magnificent drawing. Altaf deploys rags and brushes together. Nilima Sheikh’s recent paintings unfold like hanging scrolls unrolling the histories, folk legends and the once-upon-a-time magical landscape of Kashmir.

Sculpture offers potential for the third dimension in space, which has its own challenges. How do you transform inert matter into energy, give it life? No one understood this better than Ramkinkar Baij who infuses vitality into his monumental figures of Santhals striding across the earth. Radhakrishnan, his pupil in Santiniketan, takes on the challenge of conceiving figures in bronze to defy the laws of gravity: they are attenuated, pulsating with life coursing through their limbs. They stretch, gyrate and spin with their arms and legs in the air, embracing the universe.

Clay possesses a primordial quality of the earth, with millennia of tradition across the world – how do you invent anew within this familiar medium? Watch Himmat Shah working with a chisel on his pile of warm red terracotta, gouging out sections as the object slowly assumes pyramidal form, alluding perhaps to a Buddhist stupa, or to the sacred numen of stones found in innumerable wayside shrines. Sculpture has always been sensuous and tactile – observe Dhruva Mistry fondling his own creation!

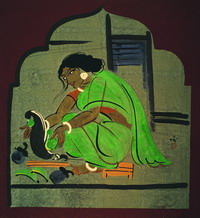

When the artist becomes one with his work, the technique dictates his posture and body language. As Jogen begins by drawing his archetypal outline, he does this on the floor by kneeling beside the paper. Vaikuntam begins as well by outlining his figures, and he too lies sprawled on the ground. Now this happens to be the manner by which I have watched patua artists paint their long scrolls by lying and squatting on ground surfaces. It cannot be mere coincidence that like them, the stylistics, outline and resource to archetypal figures inform the work of Jogen Chowdhury and Thota Vaikuntam.

Artists are certainly aware of the choices open to them. Radhakrishnan recalls a brusque remark made by his mentor Ramkinkar Baij, in Bengali. ‘If you expect your sculpture to stand out, stand up to work on it!’ This could be interpreted literally – Radhakrishnan stands as he works on his bronzes; but it implies also that the artist needs to stand on his feet, independent of support, to discover his own originality.

Infinite possibilities in technique and temperament work in tandem with body language. Vivan Sundaram sits formally dressed at a table, the legs of which are refurbished with coke and beer tins, pouring over his assemblage of beads, rings, and bric-a-brac to be pieced into an installation. Arpita Singh is at home wearing a lungi, bending over her animated water colors as she sits at a scribe’s low desk. Anjolie Ela Menon aspires upwards instead to a tall canvas and the heights of her dark shepherd girl, adorning her now with turquoise to accentuate rhythms of the body. Krishen Khanna prefers to use an easel, drawing some times with a pencil before he mixes paints on canvas.

The medium and methodology may be the same – but the results can be so different! Jeram Patel and Sakti Burman each stand over the table to mix fluid inks which flow on to the paper. The process seems similar, yet their watercolours realise into different strengths and moods. A. Ramachandran and Madhvi Parekh both work on large mural paintings on canvas; but they approach their work differently. Ramachandran, a tall man, needs to stand on a table to detail with a fine brush the sensuous sway of his lotuses – inspired from his days in Santiniketan as much as from his study of ancient murals in Kerala. Madhvi squats on the ground in the manner of village women, filling in figures within figures as they stitch traditional fabrics of a phulkari or a kantha. These images flow from the imagination; but temperament and experience schools a different grammar, a different methodology.

We begin to learn slowly, to ‘see’ differently from the artist’s perspective – to sense that compelling need to explore/ transform/ reinvent according to inner compulsions, with a sensibility that is innate to the person. This endeavour cannot be explained through words but only through body and gesture: through that silent, selective, discerning process of the hand.

Gesture is the key word, I believe, to understanding process: to follow the hand relaying ideas and perceptions to tactile surface. For Benodebehari Mukherjee in his last years the act of ‘seeing’ was poignantly transformed into sensing his way around his paper collages. Matisse took to the same resources when he lost his eyesight: paper collage is tactile, and colors can be selected, not painted. Benodebehari stands still with his hand on the wall, not groping, measuring the space around his paper cutouts which in contrast are standing, squatting and walking. The last of the great masters of Santiniketan and the first to be tutored by Nandalal Bose, he does not give up. The spirit which he infuses into a single free line dancing across white paper creates rhythm in space, bringing the image alive. We sense his spiritual kinship with the Taoist painters of ancient China, his everlasting quest for freedom of spirit.

Ramkinkar Baij searches not for effervescence and rhythm but for the monumental in sculpture. He turns with bare shoulders and profile to confront his image, rapt in concentration, oblivious to all else including the camera. Both artists from Santinketan became recluses; and these rare pictures in black and white emphasise their commitment. Above all, they each formulated an idiom of their own, guided by Tagore’s significant realisation that ‘true modernism is freedom of mind, not slavery to taste.

The vision of Rabindranath Tagore who founded the unique school of Santiniketan influenced all who taught and learnt there: to see art as personal, born from instinctual responses to the local landscape and red soil of Birbhum Bengal: of land as shared inheritance. Yet paradoxically, as history turned out, both Benodebehari and Ramkinkar were to work in and contribute to public spaces: to valorise both proletarians and tribals and to celebrate quotidian activities. These include Benodebehari’s classic murals of the saints in Hindi Bhavan at Santiniketan (1946-47) and his posters for the Haripura Congress (1939). Ramkinkar undertook the colossal images of the Yaksha and Yakshi which stand before the facade of the Reserve Bank in Delhi (1959).

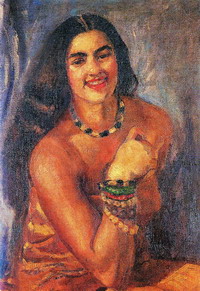

While Santiniketan under the tutelage of Nandalal Bose was deeply inspired by India’s classical heritage, a woman of charismatic personality emerged in the 1930s to become an icon within her brief life time. Amrita Sher-Gil returned from Paris trained in the modernism of Europe, contemptuous of the tame conventions of her male contemporaries. Her dual identity of being both Indian and Hungarian gave her a privileged position and a libidinous persona – which she projects deliberately in her several ‘Self Portraits'.

In the span of five years Sher-Gil travelled through the country, absorbing the poetics of Indian sensibility – influencing dramatic transformation in her own work. While her ‘Child Bride’, ‘Hill Women’ and ‘The Brahmacharis’ suggest the pervasive influence of Gauguin, her later canvases of ‘The Swing’, ‘Woman at Bath’ (1939), ‘The Red Verandah’ and ‘Woman resting on a Charpoy’ (1940) are each saturated with the vermilion reds, ochres and blue-black in early Rajput miniatures. Her paintings are of seminal importance in bringing attention to the body of the woman, projected with a sensuality to influence the work of women artists in India forty years later. Her ‘unfinished project’ on the woman’s body is continued today in works represented here by Arpita Singh, Nalani Malani, Nilima Sheikh, Mrinalini Mukherjee, and several other artists.

In black and white, the early photographs which initiated this book project include Jamini Roy, the only artist here born in the nineteenth century. His studio appears as I had visited it in 1963: pictures line the wall and are stacked on the floor, from an early impressionist landscape to his archetypal woman, the typical horse and rider and his merging of bird/animal/human figures. Conspicuously placed in the studio is his terracotta collection of Bankura horses and riders and innumerable figurines of the earth mother which were his direct sources of inspiration. The sensibility for village/rural art nurtured in Santiniketan was reinvented by Jamini Roy into a vocabulary of folk primitivism. His career coincided with the decade of nationalism of the forties, when national identity came to be represented through folk and village art – as much as it had been at the birth of nationalism in Mexico.

The forties marks the threshold not only of political ferment but also of a new consciousness in art. Bengal had suffered most with the great famine of 1942, the threat and chaos of the second World War, riots that tore the city apart in 1946, the ideological divide between Communists and the Congress. In these critical years was formed the Calcutta Group in 1943, with their first exhibition in 1945 and the slogan ‘Man is supreme, there is none above him’. Prodosh Dasgupta, Nirode Mazumdar, Paritosh Sen and Rathin Maitra were among the founding members. But the artists who were deeply stirred to chronicle the victims of the devastating famine were Zainul Abedin, Chittaprasad and Somnath Hore who expressed through their powerful woodcuts and prints, incised with the anatomy of angst and anger.

For Somnath Hore who was the youngest, the Bengal famine left permanent scars – resulting in his continuing theme of ‘Wounds’, expressed through his drawings, graphics and poignant, emasculated bronzes. The Communist Party discovered talent in him to make posters and sketches, and placed him in charge in his home town of Chittagong. Later as a student he accompanied party members to document Tehbhaga, the first organised political revolt of peasants in Indian history. Published with his notes and sketches, the ‘Tehbhaga Diary’ affirms his ideological belief in rural strength.

Both the romantic idealism of rural roots and the fire of political ideology were thrown out with Independent India, and the advent of the secular socialist republic. Coinciding in the same year of 1947 was the birth of the Progressive Artists Group (PAG) in Mumbai, a group of six urban artists declaring their manifesto as a radical break from the past and with the purpose to ‘paint with absolute freedom for contents and techniques, almost anarchic…’. They signal the transition into the contentious history of modernism in Indian art, about which much has already been written. Chaitanya Sambrani critiques the contribution of the PAG, and he makes a valid point on the mythical status assigned to them – even as some of them continue to paint into the 21st century. ‘That their work and personae have become subsumed within a myth of originality, a story of male heroes establishing the foundations of a national modernism, makes historicising both a problem and a remedy.

Away from the PAG in Mumbai, a single woman in Kolkata was sculpting heroic images in bronze, inspired by her socialist ideology of valorising human labour. Her ‘Boatman’, ‘Archer’, ‘Kite Seller’, ‘Fishermen’ casting their nets, ‘Baul Singers’, her towering ‘Cable Workers’ and her housewife threshing rice in ‘The Spirit of Daily Work’ are ordinary men and women made tall by their herculean endeavours. Learning the traditional technique of bronze casting from the Gharua artisans from Bastar, Meera Mukherjee was deeply inspired by tribal art. ‘These master artisans know not only technique but are also deeply aware of the spirit… I asked myself, can we artists, modern artists, not approach the work that we do in the same spirit? What if we build the figure not of a god but of more earthly things, can we not feel in such creation a similar spiritual unfolding?

How might a painter of modern sensibility regard his own working process? Take F. N. Souza, the most articulate of artists who wrote the radical manifesto of the PAG, and died before he could be included in this book. Insisting on his individual genius, he writes brashly on the act of painting: ‘When I begin to paint I am wrapped in myself, rapt; unaware of chromium cars and décolleté debutantes, wrapped like a foetus in the womb, only aware that each painting for me is either a milestone or a tombstone. But a foetus in the womb is a thing created… When I press a tube, I coil. Every brushstroke makes me recoil like a snake struck with a stick. I hate the smell of paint. Painting for me is not beautiful. It is as ugly as a reptile. I attack it… It is the serpent in the grass that is really fascinating. Glistening, jeweled, writhing in the green grass. Poisoned fangs and cold-blooded. Slimy as squeezed paint… treacherous like Satan yet beautiful like Him.

Born a Roman Catholic in Goa, Souza uses the metaphor of the snake/ Satan to describe how he regards (his own) painting: treacherous, ugly and yet beautiful. This is how his pictures seemed when I once visited his small unkempt room in Mumbai, the walls vibrating with townscapes in impassioned red with stark black trees leaving their indelible imprint.

Sambrani notes that three of the original six members of the PAG came from minority religions, one Christian and two Muslim; and Ara had Dalit antecedents. This may explain why they chose to take a secular stand in the most secular Nehruvian era of the fifties, and also why they put ‘modernism’ on their agenda – because both promised them emancipation from religious trappings. Yet how free were they from their backgrounds, and how much were they influenced by the modernism of Europe? As I see it, environment and personal history played indispensable roles in formulating their idioms.

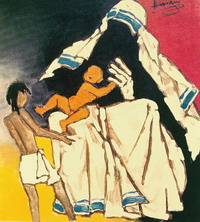

A painter of film hoardings and signboards before he joined the PAG, his background and training contributed substantially to Maqbool Fida Husain’s vocabulary of ‘signs’ – a stock repertoire that found use whenever required in his paintings. In that early extensive panel of his titled ‘Zameen’ (1952) stretching across fifty feet he valorises rural India through symbols of bullocks, farm labourers, the wheel, a woman churning butter. Later icons from the seventies and eighties depict Mother Teresa, Indira Gandhi, Amitabh Bacchan and Phoolan Devi in a take on film posters; and Madhuri Dixit who became his eternal inspiration for dynamic energy.

Now, each icon is represented through familiar signs: the unmistakable white sari with blue-border sheltering a child identifies Mother Teresa; the lonely woman running across paths characterises the relentless will of Indira Gandhi; the red bandana marks the wild Bandit Queen; dance is invested in Madhuri whose vitality inspired him to make his magnum opus on film. When his paintings of goddesses and epic women have mired him in heated controversy over the past fifteen years, we need to recall that with his background of film hoardings all icons are symbolic. They are no more or less than encoded signs of an essential humanism by which he elevates the woman as much as he does the goddess.

Husain does not hesitate to include religious images in his pantheon and figures from the Hindu epics. As is evident with film hoardings, these images are collaged together into pastiches. We watch him paint Krishna playing the flute seated on a white cow nestling under him, while Mother Teresa rises to the right side. The two icons are unrelated, but they share one identifying characteristic which is more significant than usually noted. Husain will never paint in the details of a face: he leaves Mother Teresa in shadow, and allows Krishna to be identified by his peacock feather and flute. Even as he embraces every subject, Husain follows the precepts of his own faith by obscuring that sign of human life: the individual face.

The Progressive Artists joined by their near-contemporaries: Tyeb Mehta, Krishen Khanna, Akbar Padamsee and Ram Kumar are represented here. Each artist was seized by the spirit of the times, espousing a humanism that raised the ordinary man to heroic proportions — breaking that divide between mortals and the godly. Krishen Khanna seeks narratives from the life of Christ at his most human vulnerable: Christ praying at ‘Gethsamane’, ‘The Last Supper’, ‘The Betrayal’, the ‘Pieta’, ‘Christ at Emmaus’, using light and darkness to poignant effect. At the same time he depicts the marginalised man with his anonymous labourers herded into a ‘Truck’, the ‘Bandwallahs’ in their gaudy uniforms playing out their sad, brash tunes.

Tyeb Mehta’s paintings of the underprivileged are among the most subtle, understated and powerful, rightly acknowledged now for their mesmerising presence. From his earliest depiction of the ‘Trussed Bull’ in 1954 he nurses an uncompromising rage at deprivation and exploitation. He creates tension between form and colour, depicted by that diagonal line dividing the canvas in space and dismembering the figure. The ‘Falling Figure’ hurtling headlong into the abyss, the fugitive rickshaw puller, even his atavistic goddess Kali letting out a cry evoke within us fear, tension, terror. It is only with his recent series of ‘Mahishasura’ (1998) that his quiet rage resolves into equilibrium. Tyeb sources an alternative telling of the mythic tale where the demon buffalo is worshipped in Karnataka – where he emerges now in Tyeb’s paintings as the antihero, vanquished and yet triumphant for he dies in the embrace of the goddess.

In the fifties Ram Kumar painted stark images of urban life such as the ‘The Watermelon Seller’; but after his series on Benares his pictures transcend the urban, to chart and crystallise into interior landscapes of the mind. Akbar Padamsee, the most cerebral of artists in his studies in Sanskrit and Indian aesthetics, moves from figure studies into that wide expanse of what he terms ‘Metascapes’: metaphors of landscapes. As in classic Rajput paintings of the Ragamalas and in German expressionism, he chooses colours arbitrarily to depict passion, mood and volume (dhvani). For instance, the resonance of mountains prompts him to stain them deep crimson red against sharp blues.

Unlike other members of the PAG, ‘Raza painted only landscapes’, notes his contemporary Gaitonde. Growing up in the dense forests of Madhya Pradesh and beside the sacred river Narmada, Raza’s paintings sustain an enchantment with nature and the elements. Evolving through distance and memory, his obsession distilled itself into a single leitmotif of the bindu: as the seed of life; as the ‘Black Sun’ (1953) blazing over a scorched landscape of his homeland; as energy bringing life into a celebration of nature; as the abstract mapping of his native country in ‘Ma’ (1980); as the circle symbolising the ‘Panchatatvas’, the five elements of earth, water, fire, sky and ether; as ‘Naad Bindu’, resonating with sound echoing through the universe. The bindu holds the potential for a thousand manifestations.

Unlike many artists, Raza is deeply concerned with the process of painting and its evolution, a process which he likens to birth: ‘The process is akin to germination. The obscure black space is charged with latent forces aspiring to fulfillment. Like the universal order of the ‘earth-seed’ relationship, the original form of the bindu emerges and unfolds itself in the black space.

Indian sensibility has always given primacy to the human figure in painting, sculpture, dance. Yet equally, the tradition of abstraction has persisted with persuasive power: in the abstract rendering of the human voice, in geometric yantras for meditation, in cosmic diagrams of the universe, in the salagrama, lingam and yoni as symbols of divinity, in innumerable numens or signs still worshipped in wayside shrines.

Unlike the discovery of abstract art in Europe early in the 20th century when artists had to legitimise their work process – from Wassily Kandinsky (1914) to Paul Klee (1922) right through to Hans Hofmann and Joseph Albers in the fifties, this defence never became necessary for Indian artists: they inherited the principles of abstraction as inherent to Indian sensibility. When artists Swaminathan, Panniker, Biren De, Shanti Dave, G.R. Santosh, and in Europe Raza, Sohan Qadri and Viswanathan turned to the numinous symbol, they were continuing the practice of centuries. Their contribution lay in rediscovering and merging this familiar vocabulary with the pure formalism of modern sensibility.

This predilection for abstract art evolved naturally in Tamilnadu – perhaps from that philosophical bent of mind and mathematical genius that has produced great scientists and mathematicians. K. C. S. Pannikar, Principal of the Madras Art School from 1957, set the pace for formulating a new aesthetics by adapting indigenous symbols and astrological charts into contemporary expression – but divested of their ritual meanings. This practice continued at the artists’ village of Cholamandalam, and is to be found equally in sculptures by Janakiram, S. Nandagopal and Balan Nambiar. But in my opinion the most innovative use of abstraction developed later in the ninetees in the cartographic charts by Palaniappan.

TA few artists, it may be recalled, merge both these traditions of the abstract and the figurative in their journey. Among them we would place Jehangir Sabavala as that remarkable alchemist who evolved from his cubistic figures and landscapes of land, desert and sea into meditative expanses of sky and light pared to their essence. He is on a pilgrimage, venturing out to seek the intangible, the most elusive of mysteries: expansion of inner space. ‘No longer am I satisfied with the juxtaposition of planes, the search for rare colour, the total denigration of the unpremeditated. It is the intangible which is now my goal. Space and light, and an element of mystery begin to permeate my canvases. Emotions seek a new release in what I hope will become a permanent synthesis of heart and mind.

Inevitably there had to be a reaction against the Bombay Progressives, as they themselves had reacted against the ‘vapid revivals’ of the Bengal School. This reaction rose like tidal waves from different regions of Baroda, Cholamandalam and Delhi. ‘Group 1890’ held their first exhibition in Delhi in 1963, organised by J. Swaminathan and receiving enthused support from celebrated Mexican poet and ambassador Octavio Paz. Three members of the Group, Jeram Patel, Jyoti Bhatt and Gulammohammed Sheikh, were already employed as faculty at the Art School in Baroda. This show is recalled for having re-established indigenism, claiming to present an ‘apersonal’ art. This is how Swaminathan framed part of its Manifesto, with the last sentence being almost a direct attack against the PAG. ‘The form proper is the free form: its freedom is neither the denial of its history nor its recapitulation… For us, there is no anticipation in the creative act. It is an act through which the personality of the artist evolves in itself in its incessant becoming… Art for us is not born out of a preoccupation with the human condition.

J. Swaminathan was that rare eccentric who, like Souza, could wield words as well as he explored paint, and who could spur a significant rebellion in the sixties against the heroic figuration of the ‘human condition’ by the PAG. His search for authentic indigenous roots was expressed in mesmerising fetish symbols of the triangle and the spiral, stained blood red and black, shimmering with energies. Later he was using vegetal dyes of rocks and earth on his canvas; and when I last visited him in 1992 he suddenly was struck by the resemblance of his images to DNA molecules. His curiosity was immense, his mind open to that state of ‘becoming’.

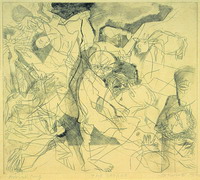

The many concerns that the 1890s Group initiated brought distinction to the art school at Baroda in the seventies. There was a return to primordial essence in clay and watercolours by Himmat Shah, in stone by Nagji Patel. One new area of research was ethnography through photographs by Jyoti Bhatt and Kaneria, with field expeditions to record festivals and folk traditions. There was an impulsive urge to explore inner resources in Jeram’s black and white watercolours; he experimented to a point where even paint is banished in his blistering blowtorch images. The ultimate finesse in minimalism was expressed by the late Nasreen Mohammedi, who left a legacy to follow for her students at Baroda.

That abstract art did not develop as much as it might have had to do with a certain pedagogy of teaching at Baroda. Encouraged by the Dean of the Art College, K. G. Subramanyan, ‘artists were enjoined in their practice to broaden their self-definitions, in some cases incorporating the roles of the art historian and cultural anthropologist’.9 I might add that art practice was influenced also by writings in Gujarati by both Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakkar. A correspondence developed naturally with the language of the ‘visual narrative’ – in itself a different way of returning to Indian traditions by embracing oral histories, folklore, literature and cultural anthropology. Narrative, the art of story-telling in its richly varied versions, became the defining trademark in Baroda for teachers and students in the seventies.

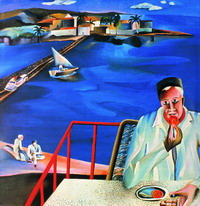

These concerns of manifesting local culture are best exemplified in the work of Bhupen Khakkar, who turned from his profession as chartered accountant and grew into a legend in his lifetime. Bhupen experimented with sources close at hand: first bazaar totems and paan shops; then he turned to his own community in their shops with garish colors of pink/green/purples, depicting small-time traders such as the ‘Janata Watch Repair’.

What made the difference was that, like Henri Rousseau in the late 19th century, Bhupen brought their aspirations and dreams to life with the ‘Man eating Jalebies’ in an erotic blue lagoon where yachts float… with the ‘Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers’ – plastic flowers was the culture which he knew. By resorting to the popular sensibility of calendar art these little vignettes become probable and poignant. Then, with increasing boldness in the eighties Bhupen began to depict his own private relationships and fantasies with brutal honesty – in doing so he moved away from the ‘apersonal’ dictum of Baroda.

Bhupen and Gulammohammed worked in tandem to recreate the cultural sensibility of Gujarat, the fantasy as well as the hideous underbelly of Baroda which continues even today, torn apart with communal violence. Sheikh’s depiction of ‘City for Sale’ is a study in vignettes of the contradictions of living in both fear and fantasy. R. Siva Kumar sums up with eloquence this dual position for Sheikh. ‘His first definitive contribution to this rediscovery of native identity came in the form of a painting meaningfully titled ‘Returning Home after Long Absence’. For him returning home meant connecting art back to a familiar world – to the environment and to the people he had left behind to pursue modernism, to the myths and stories that sustained them, to the traces of places, lives and times transmitted through their memories and histories.

The visual narrative yields to a hundred different manifestations as a means of retrieving myth, history, local culture and the environment – and therefore, identity. From the late seventies this genre grew into popular mode of expression in Baroda, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Delhi. The narrative offers scope for surreal fantasies by the late Bikash Bhattacharjee, commenting on the beautiful, the brutal and bizarre aspects of the city and society of Kolkata by meshing together the real and the unimaginable and making this combination plausible. The narrative yields to buoyant make-believe stories invented by Amit Ambalal with his give-away titles like ‘Monkeys in the Mind’. Canvases by Paritosh Sen explore the self-narrative with humour, élan and an individuality of his own making. We select three instances among the artists represented here to suggest how the narrative expresses identity and links with tradition; and yet it can be innovative and indeed subversive.

K. G. Subramanyan, gifted with a polyglot mind and a keen wit, is the third artist with Souza and Swaminathan who wrote brilliantly. His essays in Moving Focus and The Living Tradition reflect on the great masters of the past and the changing language of Indian art. He took great delight in returning to the woodcut tradition for illustrating children’s stories; and in reinventing glass painting to construct his pungent narratives filled with fantasy, violence and satire. He had revived the narrative in indigenous mediums, beginning with his murals in terracotta relief at the Gandhi Museum at Raj Ghat, Delhi. Yet again, he innovated in this most traditional medium in his reliefs titled ‘Tropies’, by using baked clay which is so appropriate to the soil of Bengal, to comment on the political tragedy and horrors of the 1971 war in Bangladesh.

The depiction of narrative is not always sharp and satirical – it can be deeply lyrical. Nilima Sheikh takes recourse to the stuff of legends and folklore built up around woman mystics and poets Meerabai and Akka Mahadevi. She paints them walking naked in their solitude, clothed only by their long hair, stepping out of the world of conventional orthodoxy and resolute upon their path of solitude. These earlier watercolours by Nilima are saturated with a redness that signifies the yearning of these women, who are hailed as saints today but were essentially fragile and vulnerable in soul and body.

Now she relies upon poetry to awaken memory and the past, and she sources the folk legends of Kashmir. She inscribes verses from the late Agha Shahid Ali, evoking nostalgia for the country he had left behind – words inscribed against the emerald blue lakes and winding rivers and mountains which wind and flow themselves like poetry down the length of her long scroll paintings. In this magical landscape are princesses picnicking under chinar trees and fabulous gins, demons hurling down stones and fakirs walking to shrines dotted across the topography of Kashmir.

The ‘stuff’ of painting, poetry and legend are infused together to recall that paradise that once was – not only for Shahid Ali but in her own childhood memories. This narrative is not linear but cyclical, returning again and again. The ‘process’ used of unrolling stories on scrolls as in Tibetan and Central Asian paintings adds to a sense of history and of time-in-continuum.

For Manjit Bawa the return to the mythic narrative became the means of returning to Indian sources when he had returned from London in the seventies. He would read from the Bhagavat Purana, that huge compendium of stories which I found always with him in Dalhousie. From studying the hill painters of Basohli and Mankot he imbibed the skill of using bold contrasts in colour optics. Why would the lyrical ambience of the Himalayas not effect a contemporary painter as much as it did artists from the seventeenth century?

From the ‘Bhagavat’ Manjit came to identify with Krishna playing the flute – as he did himself – in a symbiotic relationship with gentle white cows and wild animals breathing fire who are charmed by his music. He depicts young Krishna performing miracles of combating the horse demon Kesu, or else swallowing whole the forest fire, or dancing upon the serpent Kaliya…He paints Bahubali, glowing pink against an emerald green sea and sky as he sails through the vast space carrying the mountain of magical herbs… All these heroic feats seem to be performed effortlessly because the image is devoid of all details, glowing against a colour ground stained pungent yellow or fiery red or emerald green to infuse the mood of the narrative.

It is truly remarkable that an entire narrative is told then through a lone image pared to its essence – an image which encapsulates the whole story, or many stories from the Puranas. An image so pure and luminous in its clarity that the image becomes a vision for meditation… Manjit’s paintings are unique unto themselves in that they are both icon and narrative.

Other paintings belong to this unique genre of being both icon and narrative. That masterpiece by Jogen Chowdhury of ‘Tiger in the Moonlit Night’ (1978) sums up the mood of the Emergency: of dark nights of terror and undisclosed killings. Hailed among painters today, Jogen and Laxma Goud have each evolved a personal language that grows out of the soil – drawing from the mannerisms of people who inhabit the cities of Kolkata and Hyderabad.

Abstract art has grown with persuasive power in recent decades, moving from traditional symbols into radical statements. We trace this development here in luminous perceptions of the numen by Manu Parekh, in the dramatic divisions of space with metallic colours by Amitava Das, and in Prabhakar Kolte’s orchestration of colours that seems to be stimulated with nothing else but music.

The icon, the narrative and the abstract: each of these distinct modes of expression are seen here in the process of formulation and of practice. We are in that privileged position of being in close-up with the artist at work. One object of this book may have been to build a certain mystique about the masters at work. Yet in fact the photographs reveal more than they conceal, of the mysteries of the artist at work.

(From the book ‘Faces of Indian Art’, published by Art Alive Gallery, 2007)